vehicles and melodies. To be precise: seeing a vehicle bowling along, at speed, while a melody shouts out on the soundtrack. That, at last, is the thing that Quentin Tarantino adores more than anything; more than awful old TV appears, more than boxes of grain, more than savagery so out of control that it essentially froths, and that's just the beginning, on the off chance that you can trust it, than the delights of logorrhea. His most recent work, "Sometime in the distant past . . . in Hollywood," is an announcement of that adoration. There are numerous scenes wherein the characters—people like Rick Dalton (Leonardo DiCaprio) and Cliff Booth (Brad Pitt)— engine around Los Angeles without a consideration. To consider those scenes the best thing in the film is certifiably not a slight upon Tarantino. As he, surprisingly, knows, they are the sorts of scene that play in our motion picture recollections, years after the occasion, on a defenseless and upbeat circle.

Rick Dalton is an entertainer, pretty much. It's 1969, and he's concerned that, eventually, someone will say that he used to be enormous in pictures. He's not yet over the slope, however he's well past the pinnacle. Having featured in "Abundance Law," on TV, in the nineteen-fifties, he is diminished to playing heavies and slime balls; and their sole reason, as a specialist named Marvin Schwarzs (Al Pacino) discloses to Rick, is to be bested by the saint. Getting bested is the most exceedingly terrible. Watchers come to consider you to be nonessential. In any case, it's a vocation, and Rick enjoys nothing increasingly, even now, than plunking down with his amigo Cliff and a six-pack of cold ones, viewing a scene of "The F.B.I.," and sitting tight for the minute when the scoundrel—Rick, obviously—gets the opportunity to convey his slime ball line, with a jeer on his sleaze ball face.

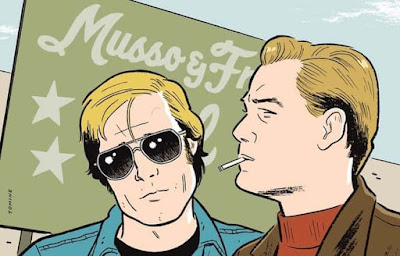

Bluff is Rick's trick twofold, in spite of the fact that, nowadays, he is by all accounts significantly more: driver, gofer, and individual consumer. He's likewise a team promoter, of a to some degree sorrowful assortment. He doesn't shake a pom-pom or anything, being all the more a shades-and-pants man, without any hysteria or uproar. In any case, he cocks a finger like a gun, point it at Rick, and state, "You're Rick screwing Dalton. Don't you overlook it." This is Hollywood, all things considered, where being overlooked can be a reason for death. One humble errand, for Cliff, discovers him high on the top of Rick's home, on Cielo Drive, fixing the TV reception apparatus. It's broiling up there, so he sticks a jar of lager in his device belt and strips to the midsection. Devotees of Pitt will fan their foreheads and review his appearance as Will, on "Companions," in 2001, during which, amidst a debate, Phoebe shouted, "Gracious, please, Will, simply remove your shirt and let us know."

I thought, in those days, what a smooth and unrushed humorist Pitt could be, entirely quiet with the disorienting impact that he had on different spirits, and it's been unsettling, from that point onward, to see him secured into such a large number of jobs that give him just an erratic opportunity to be entertaining. Recognition be to Tarantino, at that point, for allowing Pitt the time and the scope to spread out his affableness, and for ensuring that no bend in the account, anyway threatening, is sufficient to invalidate his grin. The outcome is one of Pitt's most including exhibitions, favored with wraparound beguile, unequivocally in light of the fact that Cliff never attempts to get excessively profoundly included.

At some point, for example, he grabs a high school drifter by the name of Pussycat (Margaret Qualley) and gives her a ride to a farm out in Chatsworth, in the San Fernando Valley. She lays her head in his lap as he drives. It's dreadful and dusty at the farm, with a troop of young ladies as youthful as Pussycat, in addition to an elderly person (Bruce Dern) who professes to be visually impaired yet prefers to sit in front of the TV. We hear notice of Charlie, whoever he might be. Something is massing noticeable all around, similar to roar. Precipice's tire is cut, and we dread for his security, out there in the half-wild, yet he makes it home fine and dandy. Gracious, and incidentally: Charlie's last name is Manson.

At whatever point you go to a Tarantino film, you leave away with the inclination that history is one inch thick. The slimness is a piece of the good times. Kid, does he know each portion of that inch—each film notice in the saint's home, each bulletin next to the street, each business on the radio. ("Paradise Sent, by Helena Rubinstein.") Rarely has the strutting of such learning appeared to be progressively twisted. Look at Rick, alone in his pool, skimming in an inflatable seat and crowing along to "Snoopy versus the Red Baron," in this way affirming the teaching of film as Pop craftsmanship: the more immaterial the detail, the more triumphant the executive's merriment at culling it from blankness. For what reason must Cliff live with his pooch, Brandy, in a trailer behind the Van Nuys drive-in? Since the area permits Tarantino, similar to a theater chief, to put a title on the lit up sign. "Woman in Cement," it peruses. "Forthright Sinatra. Racquel Welch." The name is really spelled Raquel, yet I wager you the mistake is intentional.

What turned out to be clear, from Tarantino's "Inglourious Basterds" (2009) and "Django Unchained" (2012), is that he's never again content with the recovery of random data, fashioning a style from the pieces of a devouring society. History is likewise there for the tweaking. In this way, in the first of those stories, Hitler is killed before the finish of the war; in the second, a previous slave demolishes an estate. (In the two cases, fire is the purifier, and it flares again in the new film.) While numerous spectators delighted in the ruin, a few of us jumped at its suggestions. I believed I was being drafted into the vengeance dreams of a blazingly talented immature, or of a significantly more youthful kid, exciting the play area with yells of "How about we execute Nazis!" to put it plainly, Tarantino is the perfect inventive nonentity for a period wherein the old-school need to investigate past times, or to contend over them, is being bested, with the guide of innovation, by the all the more invigorating inclination to redo them as we want.

Thus the title, "Some time ago . . . in Hollywood." It echoes "Quite a long time ago in the West" (1968) and "Some time ago in America" (1984), both coordinated by Sergio Leone, whom Tarantino venerates. In any case, that demure ellipsis is uncovering. It advises us that "Sometime in the distant past" is the means by which fantasies begin. The movie producer might be determined to get everything directly around 1969, down to the sounds and scents, but at the same time he's intriguing us to smoke a little misleading quality. Rick's neighbors, for instance, are Sharon Tate (Margot Robbie) and her better half, Roman Polanski (Rafał Zawierucha), and we watch them celebrating at the Playboy Mansion, together with Steve McQueen (Damian Lewis) and different famous people. All impeccably conceivable. The way that Tate was killed by individuals from the Manson pack, on August 9, 1969, on Cielo Drive, is additionally a matter of record. For Tarantino, be that as it may, records are made to be broken.

VIDEO FROM THE NEW YORKER

Crossword Puzzles with a Side of Millennial Socialism

The motion picture is a whole deal, running more than more than two hours. There's an outing to Rome. There's an unbelievable, if unnecessary, fight among Cliff and a haughty Bruce Lee (Mike Moh). Furthermore, truly, there's a section for Nicholas Hammond, who was Friedrich in "The Sound of Music" (1965), as the excited executive of a Western. From time to time, you get a sense, similarly as with "Mash Fiction" (1994), that, in Tarantino's ache to engage, he is making a decent attempt—striking frames of mind for the straightforward purpose of cool, and urging his players to push the breaking points. Rick Dalton is a quite awful entertainer, and DiCaprio, an awesome on-screen character, strains each and every fiber to perform that insufficiency; the scene wherein Rick, having botched his lines on set, lays incensed waste to his trailer strikes me as a guilty pleasure, however DiCaprio's fans will without a doubt hail his passionate bombast. Unmistakably all the more winning is Rick's discussion with a tyke star (Julia Butters), an eight-year-old follower of the Method. Not since Henry Spofford III, at a comparable age, hit on Marilyn Monroe's character, in "Honorable men Prefer Blondes" (1953), has giftedness been such a gas. Who'd have speculated? In the wake of absorbing grown-ups blood, in film upon film, Tarantino ends up being incredible with children.

"Sometime in the distant past . . . in Hollywood" utilizes the administrations of a storyteller. In the later stages, particularly, he shepherds us through insane happenings just as, without the quieting direction of his voice-over, the different bits of story would fly separated. That dread of discontinuity will be commonplace to perusers of Joan Didion, who, in the title article of "The White Album," reports firsthand on the period, and the very spot, that Tarantino presently watches. "A psychotic and tempting vortical pressure was working in the network. A bad case of nerves were setting in," she composes. With respect to the day after the slaughter, on Cielo Drive, "I additionally recall this, and wish I didn't: I recollect that nobody was astounded." What Didion checked and enrolled, more reliably than any other person, were blames in the hardware, conduct and neurological, of a whole social structure. Tarantino might look for similar nerves, however just in sparkles and glints do they appear through the sheen of his motion picture, and two things alone cracked me out. One was the abrupt, crazy burst of severity that is dispensed by men upon ladies. What's more, the other was the response of the general population around me in the hall to that giant. They chuckled and applauded. Nobody was astounded. Some anxiety have turned into a joke.

No comments:

Post a Comment